He’s easily noticeable at school for his giant, fringed eyes

and his exuberance. He’ll jump on you with his skinny arms stretched and mouth

wide, displaying all of his baby teeth.

“Good morning, Abraham!” you’ll say, and he’ll respond with

his high-pitched voice.

“Good morning!”

Then he’ll pull your head down to his level, if you don’t

pick him up so his skinny monkey legs wrap around you, and tell you he’s

hungry.

“Mwen grangrou!”

Then you’ll assure him he can go to the kitchen to get a pre-class cracker. He’ll

receive another cracker later in the morning with the rest of his class, a

simple Haitian bon-bon sel (similar

to a Saltine) dolloped with manba (peanut

butter.)

Sometimes he’ll accept this with continued foxy grin;

sometimes he’ll nod his head sadly, those round quarter eyes heavy with tears.

When he gives those eyes you can’t help but cuddle him close, letting him wrap

those skinny legs around you and nestle his head on your shoulder, noticing

again that you don’t even notice his weight.

Abraham is in the four-year old class. Abraham is six years

old. Abraham is thirty-three pounds.

Several weeks ago Abraham missed school. For an entire week.

His chair was empty and the halls devoid of his squeaks. The

courtyard missed his mischief and instigating of tag and play.

Madame Beverly and Madame Rose noticed his prolonged absence

and wondered where he was. We considered the recent rain, several nights in a

row of heavy downpour that would have flooded the lowlands and wash near

Abraham’s house. That same wash was a churning brown mass in the hurricane,

carrying away the old bridge in its raging froth. These days it’s usually just

a trickle of muddy water coursing down the ugly blackened riverbed, safely

spanned by the shiny new bridge. Abraham’s home is on the other side of that

bridge, around the corner and up a dirt trail.

I knew that already, just as I knew Abraham’s Papa is

unwell. The few times I’ve seen him over the past ten months of school he has

been unkempt, to say the least. Many of our parents do not have the means to

support themselves or their children, and thus we should not expect them to

appear well-dressed or perhaps even well-groomed. But the longer you stay in

Haiti the more you observe the pride in appearance. This is not an unfounded

pride. This is not an extravagant pride. Rather, this is an effort to present

oneself well in the only way one can. When you have no control over your

circumstances, no guarantee of medical care, of school coverage, of food—the ability

to control your appearance becomes much more relevant.

“When I first came,” Beverly remembers, “the parents were

timid. Their heads were hung low. The children were dirty and their hair wasn’t

done.”

Now, our parents stand with pride.

They greet us at the gate. These mamas and papas are pleased

to see us and proud of their children in their orange and navy. Our little

girls have well-styled hair. Some are in elaborate braids, some are gathered

into thickly bunched pigtails, but they are all styled. The boys are neat with

shirts tucked into their wee belts and hair cropped close to their heads. They

are pressed and presentable. You cannot tell whether this little girl treks

down from her family’s tin and plywood house on the mountain or whether this

little boy has come from the eight by ten room he shares with six family

members. They are clean and they are pleased. Their guardians have taken the

care to send them out well. And when those guardians pick up their charges,

they present themselves well, also.

Not Abraham’s Papa.

He shows up to school in jeans so full of holes they present

more skin than denim. He’s dirty and unkempt, long hair sticking out in clumps.

When he’s signed for Abraham’s report cards he has printed his name in a large

unruly hand. Everything about him speaks of carelessness.

We know that Papa has problems. We know that he comes from a

broken home.

His mama walks the road in front of our school shoeless. She

is scantily clad in a loose dress. Sometimes she carries a bowl or a basket.

She mumbles to herself, shuffling back and forth. She’s aimless. She’s mentally

ill.

This is the mother of Abraham’s Papa. There is no telling

what his childhood was like.

Now, Papa is an alcoholic. Papa hardly ever works. Of

course, we know many of our papas are without work. They spend the day seeking

jobs and sometimes find paid labor. Sometimes they don’t. Many of our papas are

angry, frustrated and humiliated at their lack of ability to provide for their

families. However, they continue to try. And we see the care they lavish on

their children.

We don’t see that with Abraham.

After he’d missed school for a week, we drove over to

Abraham’s house. We parked on the corner of National Road 2 just past the

bride, and climbed a narrow dirt path. To the left were the lowlands that had

been flooded for weeks. Up the hill the ground was dry and a steady breeze

continuously shook the trees shading us. The air was very pleasant.

We passed one concrete house complete with porch and pick-up

truck in front, then arrived at Abraham’s house: a plywood and tarp aid-built

structure. The door was shut. We continued following the trail beside and then

behind the house, coming to the top of an embankment. In the hollow below were

two other houses and an open yard space. Seated outside were a woman and a few

men, all thin and casually half-dressed. We called for Abraham.

“Abraham! Abraham!”

We heard his answering response, the wee little voice

calling “Letil! I’m here!”

Then from the bushes below appeared his little head, foxy

grin splitting his face. He trotted forth and came up the hill to us, greeting

us with stomach first.

Rose, Beverly, Nicole, Jonas and I showered him with

greetings. Beverly scooped him up.

“Abraham! How are you? Kouma

ou ye? Where were you? Why did you miss school? Poukisa ou te manke lekol?” we asked.

“Ou te malade? Were

you sick?”

Abraham nodded his round head, eyes unfocusing. He stared

out from his high place in Beverly’s arms. Abraham was always difficult to

follow, logically, and today he was less responsive than usual. He assented to

everything we suggested, which seemed suspicious.

We called down to the neighbors sitting below, Rose asking

them why Abraham had been absent.

An older neighbor man came up the hill to us with

information.

“We had a lot of rain and the river got big,” he explained. “Abraham

played in the water and got a cold.”

We could accept that. More troubling was his extremely

distended abdomen and twig-like arms and legs. They were more pronounced than

ever.

“Has he been eating?” we asked.

At school, Abraham ate not only the peanut butter crackers

but a heaping plate of the Feed My Starving Children manna pack rice and beans

we serve every day.

The neighbor continued to explain that the young lady down

the hill, Madame Junior, had been sharing food with Abraham because he didn’t

get any from his own home.

Looking down, it was easy to see that Madame Junior didn’t

have much herself. She was a young lady, very thin, and surrounded by men.

Surely she was responsible for cooking for all of those who lived here. None of

them appeared well-fed.

“Is Papa here?” we asked Abraham.

“Li pati. He went

out,” Abraham answered. The neighbor confirmed.

“Abraham,” Beverly said, “you have to come to school on

Monday. We have medicine for cold. We have food.”

Madame Rose instructed Abraham in Creole.

We left him with lollipop stuck in his mouth, a treasure

from Nicole’s bag. He unwrapped it with his dirty fingernails in ecstasy, eyes

brilliant.

On Monday Abraham came to school. We weighed him. He was

thirty pounds. His records dictated he was actually six years old, despite his

placement in the four-year old class, and in March had weighed 32.4 pounds.

Beverly promptly messaged a doctor friend with this information.

The doctor responded Abraham was suffering acute

malnutrition and needed immediate intervention. He must gain 5 pounds before

vacation or the malnutrition would progress and he would die.

Fortunately the same doctor presented aid.

She made arrangements to get us a dietary supplement called “Plumpy

Nut”: a special peanut butter packed with extra nutrients, protein and sugar

that should plump up our little Abraham.

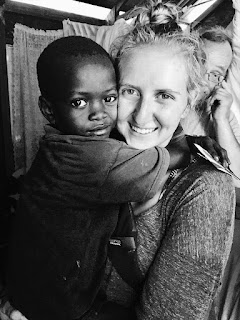

We got the peanut butter (manba) and began the regimen. The first week we were blessed with

our guests Jaimie and Phillip Bolt from Virginia. Jaimie, whose heart is as big

as the Blue Ridge mountain range, made Abraham’s feeding her mission.

Every morning she scooped him up in the courtyard and held

him on her hip through our teacher devotion. Then she set him down on her lap

in the office and fed him his crackers and peanut butter.

Because of his severe malnutrition and prolonged lack of

food, Abraham’s stomach had shrunk. After a few bites he slowed down

considerably. Eating was an effort.

But Jaimie persisted.

“We built towers with the crackers,” she said.

She and Abraham played with the food, and she cuddled him

like a baby in her lap, talking to him with words he couldn’t understand, with

all the love he could absolutely understand, and kept with him until all the

food, two packets of peanut butter and several crackers, had been consumed.

She repeated this in the afternoon. Every day that week. The

doctor had ordered Abraham eat two packets of manba in the morning and two in the afternoon, along with his usual

heaping portion of rice.

The first attempt to send the manba home did not succeed.

The manba was consumed, but not by Abraham. By Papa.

Beverly and Rose made another home visit. They met with

Papa. And Rose, in her authoritative, fear-of-God voice, explained to Papa

Abraham must eat.

“If he does not eat,” she said, “he will die.”

How much more blunt can one be? What other words need you

say to convince a papa he must care for his child?

School is finished for the summer. All of our children have

now lost the dependable daily meal. They have lost the constant access to clean

drinking water, to medicine, to affection, to a safe place. We pray in faith

that God will provide for each one of His precious lambs during this summer,

providing them with a safe place, with attention and affection, with clean water

and nourishing food.

We pray for Abraham. We pray for his Papa.

Last week we visited again.

While the team from Beverly’s home River of Life San Antonio

church was here, I took a group to Abraham’s house. He is to be weighed every

Monday, and given the next week’s installment of two daily Plumpy Nut packets.

So we took the scale along with the manba, parked the car and climbed the hill.

We called for Abraham at the crest of the hill, Madame Rose, Douglas, Nicole,

Nico, Gabby, and myself.

I chuckled as the bushes down below shook and a wee little

voice responded.

Then Abraham came out from those bushes with his foxy smile

and trotted up the hill to us.

“Abraham! Bonjou, hello! How are you?” we all greeted him.

“Abraham, did you eat all the manba? You ate it? Not Papa?”

I asked him. He said yes.

Today, Papa could confirm.

He appeared out of the house down below, grinning up at us

with a wobbly expression and a matching gait.

Madame Rose ordered him to join us.

“You see we’re standing here,” she said. “You see Abraham!

Come up!”

Papa harbors a fear of Madame Rose, and summoned the

fortitude to climb the hill in a rollicking fashion.

He managed to crest the hill, to my relief and surprise; I

was half-expecting him to overbalance and crash back down the bank. He was

clearly intoxicated.

Instead, Papa seated himself down on an overturned bicycle

lying nearby. He carried a shirt but was not wearing one. His hair was uncombed

and stuck up as usual. Around his neck was a Rastafarian necklace. He looked

like a bum: unemployed, unengaged, unkempt, unwashed, and drunk.

But he sat down and responded to Rose’s questions. He

confirmed that Abraham had been eating his manba. However, to our chagrin, when

Abraham mounted the scale, he weighed 32 pounds. The week previous he’d weighed

in at 34—almost meeting the doctor’s summer requirement.

“Why has he lost weight?” we asked, Rose addressing Papa in

her continued boss-tone. “He’s lost two pounds!”

Papa’s eyebrows shot up, the goofy expression erased. He

looked the fool who’s been struck with harsh consequence, the student disciplined

by the teacher, the catcaller slapped with a harassment charge. But he looked

sincere. Abraham’s weight loss was an unpleasant surprise.

Papa didn’t have an answer for the missing two pounds.

So Rose again repeated the importance of Abraham eating the

manba, of the precariousness of his health. His stomach was still distended so

his little tshirt couldn’t cover his torso, and his arms and legs were still

twig-like.

We then asked about church, because all conversation turns

back to God. Did Papa attend church? Was he converted? Papa said yes, he

attended, and yes, he was converted.

It was time to go. Before departure we always pray.

We gathered into a circle, and I gestured for Papa to join

us. “N’ap priye,” I said, with hand

extended toward this gangly, dirty man on the bicycle.

He giggled, shaking his head.

“Oh!” I said, “You don’t pray?”

Papa mumbled something unintelligible.

Madame Rose entreated him as well. Enough that Papa shook

his head and put on his shirt.

He joined us in the circle, and Nico prayed for us.

Then we hugged Abraham goodbye, gave him the bag of manba to

give to Madame Junior, his caregiver, encouraged Papa to go to church, and

reminded them we’d be back next Monday with more peanut butter, and the scale.

As we walked away, Abraham sucked the lollipop Nicole had

given him, and turned away to undo his zipper so he could pee on the ground

where we’d been standing. Papa was still sitting on the bicycle.

Nico and Douglas were angry. Perhaps furious is a better

description.

They were furious with Papa.

I understood their anger. But Beverly and I agreed later we

could not harbor anger for this man.

“I’m angry at the situation,” Beverly said.

We are angry for the circumstances that this man has faced,

for the life he’s known that led him to be drunk at 11 o’clock in the morning.

That led him to watch his six year old son losing the few precious pounds he’d

gained.

Nico shared at the team devotion that night. “We need to

make it a point to pray, diligently, for Abraham and his Papa.”

He faced Douglas, who was still bristling, “Bro, I’ll get

down on my knees with you every day to pray for him.”

So as we closed the devotion in group prayer, Nico did pray

for Abraham and for his father. We pray hope for him. We pray that deep-rooted

fear of God that prompted him to don his shirt before prayer would rise up.

That he would attend church. That he would be led to men strong in the faith,

wise and encouraging, who can guide him. We pray he can find honest labor and

provide for his son. We pray he would appreciate the severity of Abraham’s

condition and take care of him.

We pray Abraham will continue to eat and gain weight.

This last prayer we know is already being answered.

On Wednesday Beverly and a group distributed rice and beans

to the community. They gifted ten bags to Madame Junior, setting her face

alight with smiles, with joy and gratitude that she is valued and remembered.

She will help Abraham. Praise God that we could help her.

Please join us in praying for Abraham and his Papa.

His story is so common in Haiti—a child simply wasting away

due to lack of food. A child with parents incapable or unwilling to care for

him.

Thank God that this is one more child not forgotten, but

valued and remembered and fought for.

I don’t know what the future holds for Abraham. I don’t know

what God has planned for his father. I don’t know how many more children we may

yet encounter with malnutrition.

I do know that we cannot lose hope. I do know that wrath has

no benefits. I do know that God loves and cares for each one of His precious

lambs. He knows them by name and knows their histories and their futures. His plan

is so much greater than any of ours. Any of mine.

His plan connected us with a doctor, with Plumpy Nut, with

two compassionate ladies to feed Abraham, with many arms to cuddle him, with a

heart full of joy and vivacity despite his devastating circumstances.

May God fill us with the same joy that lights Abraham’s

round eyes and fuels his foxy grin. May we return to Petit Goave in September

and greet an Abraham running on strong legs who may not break the scale but

will tip forty pounds.

I so look forward to that day.

Isaiah 40:11

He will tend his flock like a shepherd; he will gather the lambs in his arms; he will carry them in his bosom, and gently lead those that are with

young.

Ezayi 40:11

Tankou yon gadò, l'ap okipe mouton l' yo. Se li menm k'ap

sanble yo. L'ap pote ti mouton yo sou bra l'. Tou dousman l'ap mennen manman mouton ki gen pitit dèyè yo.

No comments:

Post a Comment